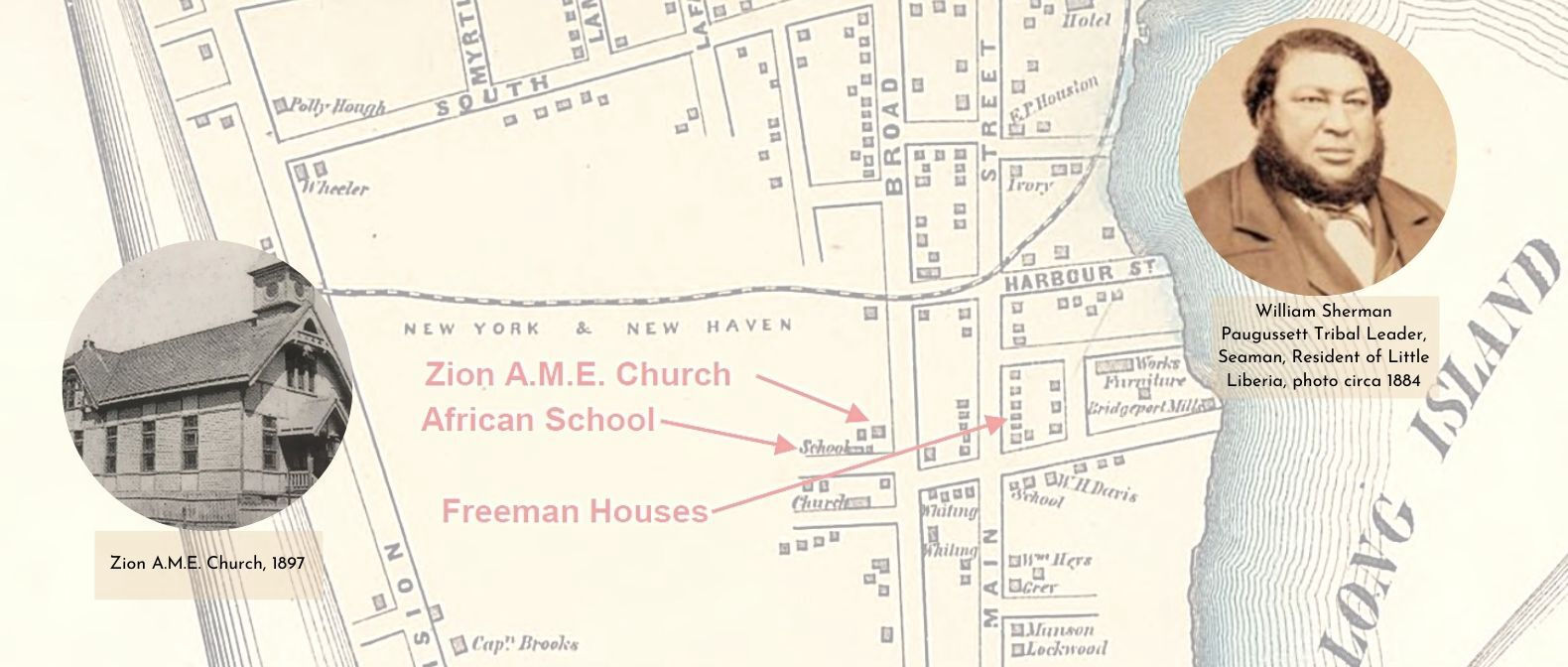

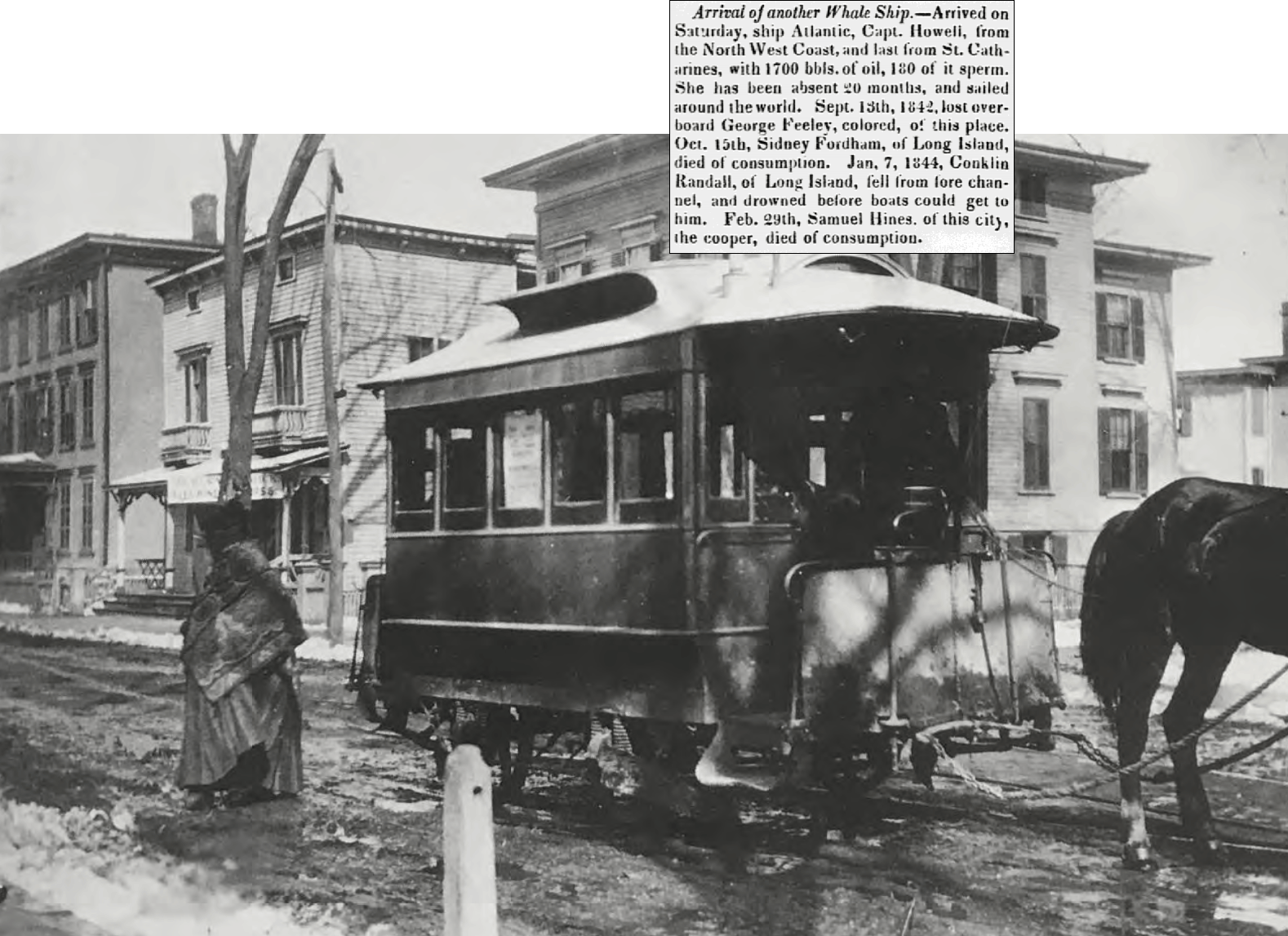

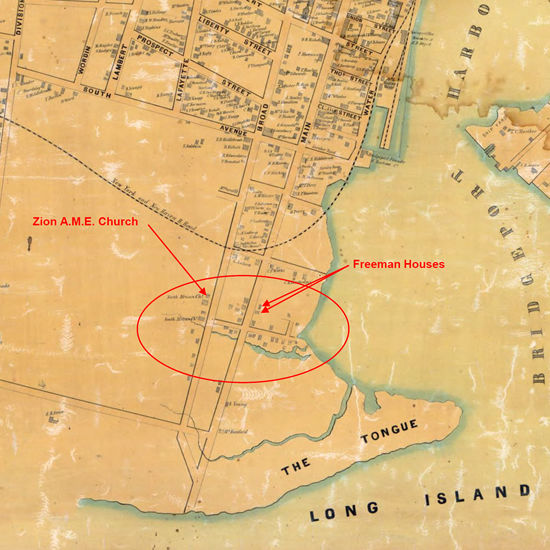

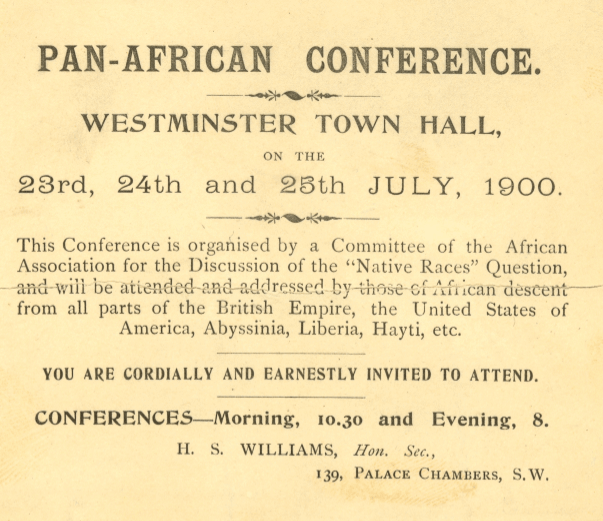

Research suggests that Little Liberia’s African and Native American residents sought to establish a free city for people of color – on American soil – during slavery in Connecticut and the US. Men brought their earnings home and then returned to sea. Many women owned or operated family business ventures; developed, owned and maintained property; and exercised leadership skills – at a time when women in the United States didn’t even have the right to vote. Little Liberia’s residents were outspoken advocates for human rights; and like-minded free people of color from around the country, indeed around the Atlantic, joined this 1800s community, and invested here.